In the early 1980s, Nathalie Du Pasquier became a founding member of Memphis Milano, the irreverent postmodern architecture and design collective started by Ettore Sottsass. Throughout the decade, the group dreamed up eclectic furnishings, patterns, and objects under the motto “form follows fun,” bucking pared-down modernist conventions for a rules-be-damned approach that balanced experimentation and exuberance in equal measure. Du Pasquier, who hails from Bordeaux, mostly designed “decorated surfaces”—textiles, carpets, and plastic laminates noted for a visual language of playful patterns and bold strokes.

Despite her indelible mark on Memphis, Du Pasquier departed the group in 1987 to focus on painting. She began with figuration—crisp still-lifes based on careful arrangements of everyday objects. Eventually, she turned to abstraction, imbuing her works with visual cues inspired by travels to Africa, the ornamentation of the Wiener Werkstätte, art by Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant, and Novecento painting by Giorgio de Chirico and Giorgio Morandi. She soon modeled her still-lifes on 3-D wood assemblages that she built herself. “I’m not so good at building,” she admits, a revelation that led her, in 2012, to try something new. Using colored pencils, she sketched freeform geometries from her imagination that, as she put it, “would never stand in real life. I don’t know why it took me 30 years, but all of a sudden I understood that I didn’t need to do all these models. I could just go straight on the paper or canvas.”

These gradual stylistic shifts are the subject of a new exhibition, “Spaces Between Things,” on view virtually at Pace Gallery through June 30. The show features two of the 63-year-old artist’s recent abstract paintings alongside earlier works that demonstrate her experiments in the medium across two decades. Taken as a whole, the assortment illuminates the inner workings of a tirelessly curious creator who, no matter the medium, “renders the dazzling complexity of simple things and coaxes out enchantment from forms hiding in plain sight,” writes Oliver Shultz, curatorial director at Pace Gallery. “She uses abstraction to invent maps for expanding the possibilities of our seeing.”

To that end, Du Pasquier takes near-full ownership of how her work is shown. “Whenever and wherever she exhibits, she smells the space and transforms it into a natural setting to host her creatures,” says the curator Luca Lo Pinto. When preparing to send her paintings to galleries, she would often frame them herself, but found that galleries removed them during installation. She now paints frames directly onto her canvases or surrounding walls to create a trompe l’oeil effect that makes the boundaries of her artwork indistinct.

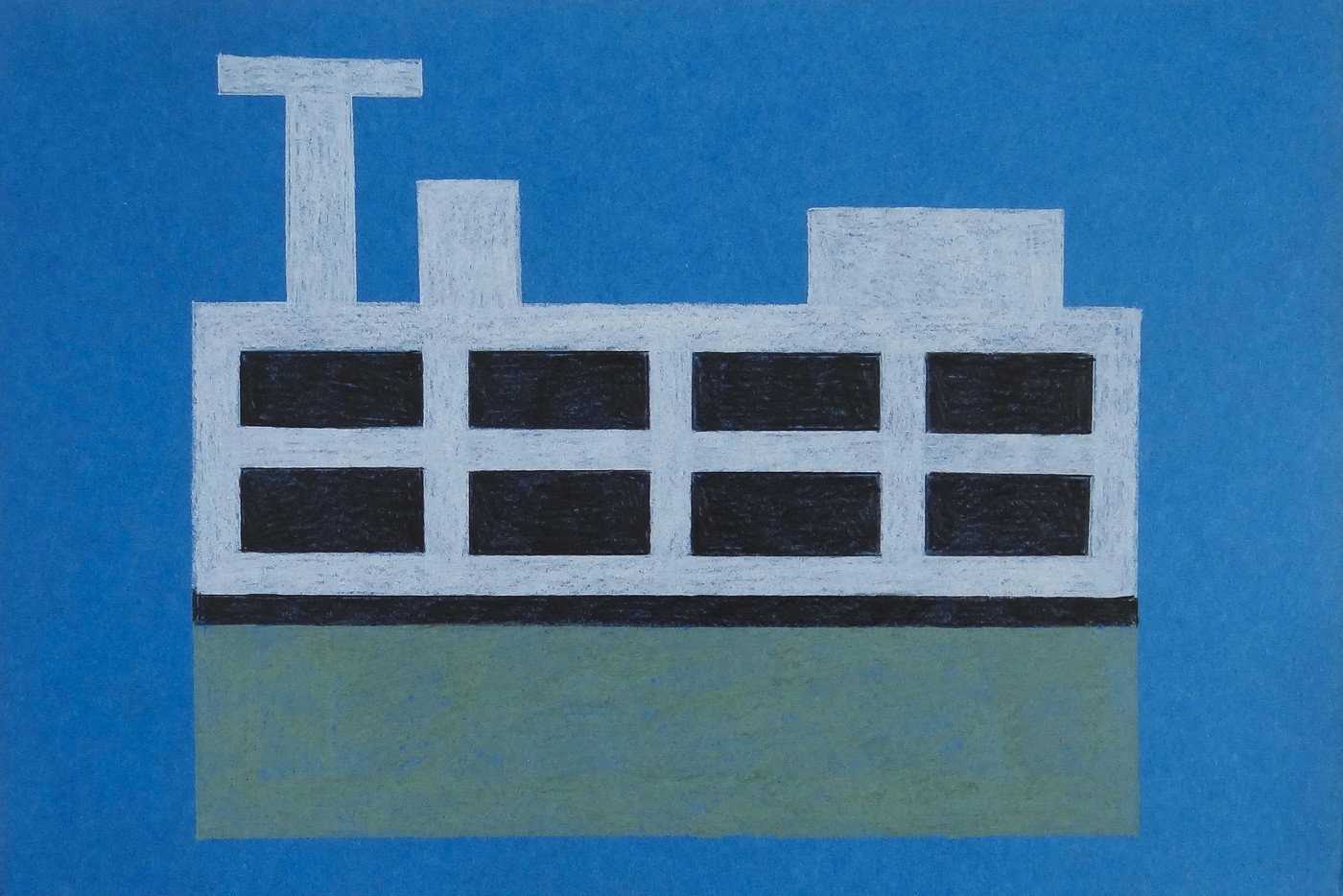

Such interventions extend to “Spaces Between Things,” in which colorful frames surround photographs of Du Pasquier’s light-filled studio in Milan, where she has lived and worked since 1979. It’s here where she sheltered in place during the coronavirus pandemic, which has forced Italy into a virtual lockdown since March. During three weeks of the quarantine, she completed a series of colored pencil drawings on blue paper while her day-to-day was confined indoors—a change of pace that made it difficult for her to concentrate on large paintings. “I found it more comfortable to sit at my table and make these drawings,” she explains, which feature in “Message from My Room,” a concurrent online show at Anton Kern Gallery. She describes the drawings as miniature versions of her paintings.

Though Du Pasquier has parted ways with design, an attention to space resounds within her oeuvre, which has also come to encompass sculptures that effortlessly toe the line between art and architecture. Take a recent series of glazed brick “towers” at the headquarters of Italian ceramics brand Mutina: At first, these structures suggest her abstract paintings enlarged to three dimensions—bricks and their perforations have long been recurring motifs in her work. Du Pasquier, however, feels otherwise. “I know nothing about bricks,” she says. “It has nothing to do with a painting, which I can alter down to the very last second.” Totemic in structure, these brick towers recast the humble building material as a crucial cornerstone of architecture.

Courtesy of Surface