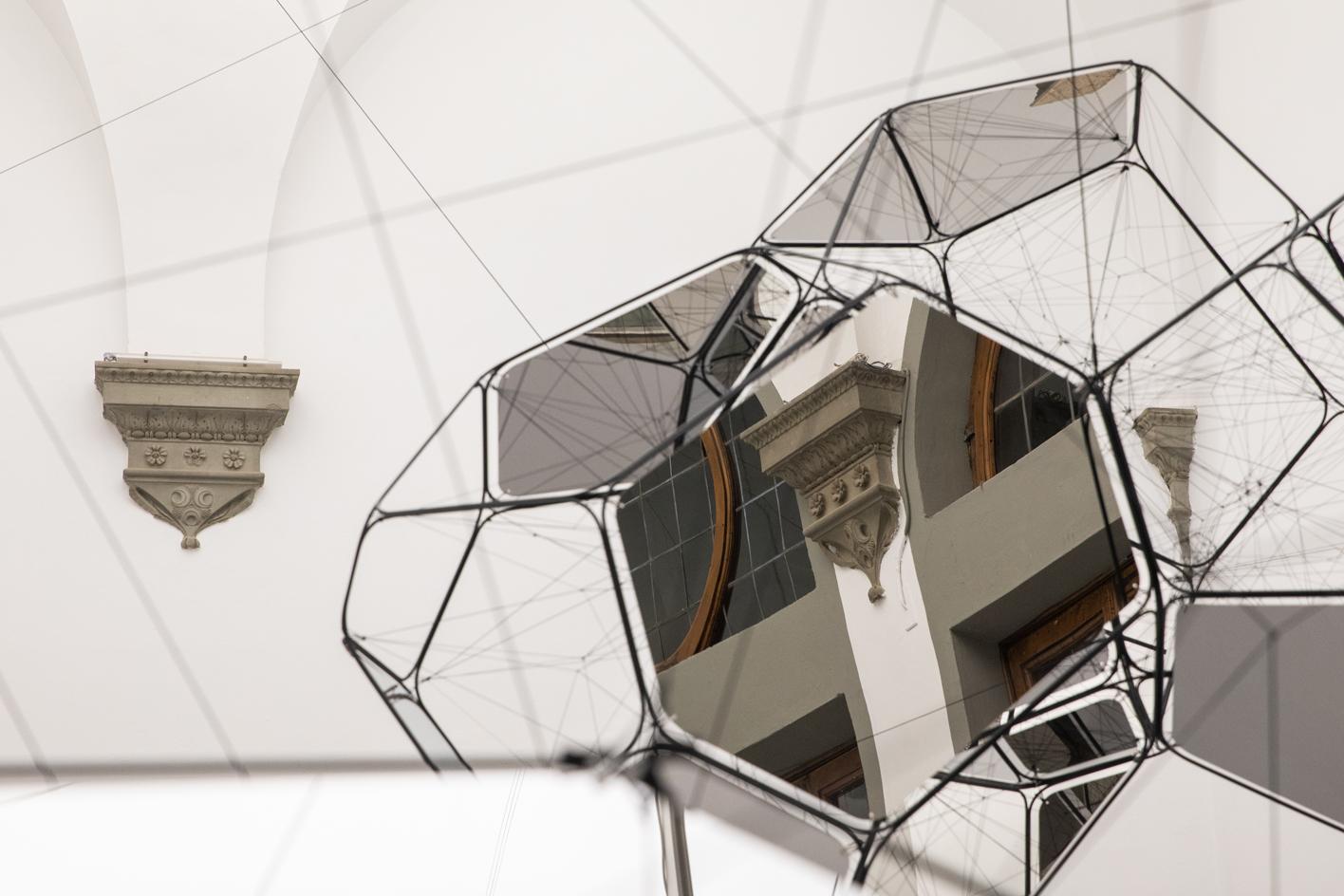

Are you arachnophobic?’ I’m asked before entering ‘Aria’, the new Tomás Saraceno exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi in the heart of Florence. The Argentine installation artist known for his environmental concerns has turned the webs of spiders into objects of monumental significance – a way to meditate on the ‘new potentials of urbanism’ in an era of ecological upheaval.

Saraceno is using the exhibition to ask: ‘If spiders could speak our human languages, what would they communicate to us?’

The artist keeps many spiders in his Berlin studio. In large glass tanks, he allows different species, sourced from habitats all over the world, to weave their webs together in unison.

Once these organic, architectural imaginaria are deemed complete, Saraceno carefully douses the webs with light-sensitive dust. In Florence, in an entirely darkened room, the contents of the glass cases are lit by spotlights installed below.

A single live spider is present to welcome the crowds. He sits entirely still in a humble corner of his web. His legs are as thin as the strands that surround him. He can’t possibly, one assumes, navigate – or even have a concept of – the great world he has created here for us to study. Yet his creation is awe-inspiring. For Saraceno, the tiny spider’s web might allow us to consider ‘another infrastructure, another way of living on this planet.’ They are, he says, potential pointers towards ‘future cities.’ Spiders are feared. Their webs are reflections of our deepest psyche. They haunt our dreams and populate our metaphors, from the ancient myths onwards – like Neith, the Egyptian Goddess of weaving, or the Greek goddess Arachne, who was depicted as half-spider half-human in Gustave Doré’s illustration of Dante’s Purgatorio. Today, massive spiders pick their spindly legs between skyscrapers in Hollywood blockbusters or cling to female forms on our advertising hoardings. They have been used, often to terrifying effect, by some of art history’s greatest practitioners. Most notably by Louise Bourgeois as allegories for her abusive mother, but also by Otto Henry Bacher, Vija Celmins and Candace Wheeler, and on film by Ingmar Bergman and Denis Villeneuve.

Courtesy of WallpaperMag